a phd is more than just the research

Around the Christmas of 2021, towards the tail-end of what would’ve been nearly two years of the Covid-19 pandemic, I came across this blog post by Austin Henley, which ended up being one of the most influential bits of writing I read during my PhD. If you’re reading this and haven’t already done so, I very much encourage you to go back and read his post at some point.

About two years ago and roughly 4.5 years after I joined Ian Duguid’s lab as a PhD student, I graduated. If I’m being completely honest, at the time I didn’t feel particularly proud or accomplished. I felt tired.

But, fatigue aside, I had learned a heck of a lot, and it was time for me to log into every service provider, bank account and government agency I could think of and change my title from “Mr” to “Dr”.

I was pretty lucky with my PhD. I had an incredible supervisor. I got along brilliantly with my colleagues. My project was super interesting and I was able to make my own. Most of my challenges came mainly from the fact that doing a PhD is hard. They really don’t hand those things out.

Also there was a global pandemic going on, which didn’t help.

I think that most of what I’ve actually learned during my PhD really had little to do with neuroscience per se. I mean, yes, obviously a lot of what I learned did have to do with neuroscience, but it was by no means all there was to it. The PhD, I think, is a pretty unique time, and one that doesn’t quite resemble what comes before nor after.

Here I list a few of the things that I learned during my time as a PhD student in the hope that you’ll find them useful, whether you’re just starting out on your PhD or are well into it. Of course, these are all relevant to what my PhD was like, so take it all with a bucket of salt; your mileage may vary.

- Take ownership

- Plan, plan, plan

- Every meeting needs an agenda

- Let failure wash over you

- Bite more than you can chew

- Keep a research journal

- Show up

Take ownership

It sounds fairly obvious, but your PhD project is your PhD project.

The harsh reality is that nobody is going to care about your project as much as you do. Your supervisor is likely managing multiple projects, your colleagues have their own work, your friends and family have their own lives and at best only sort of understand what you’re doing. All these people probably care about you as a person and have vested interests in your success. But they ain’t the ones that have to do the doing. This is going to be on you.

What this means is that you’re going to have to be the driving force behind the project, not just practically (i.e. doing the experiments) but also intellectually. Your supervisor is there to provide guidance and support, but it’s up to you to you understand what it is that you’re doing and why.

This is what really sets the PhD apart from any other degree. Nobody’s there to tell you what you need to do - and quite frankly you really don’t want them to.

When you’re only just starting out, this is going to be very intimidating indeed, especially if you aren’t coming into your PhD with a whole lot of experience in the field. I found the first year of my PhD to be the most difficult just because of how overwhelming it all was. It can be hard to know what’s expected of you, and whether what you’re doing is enough and even whether all this is really for you. Taking ownership of your project at a time where the only thing you’re sure of is that you have no idea what you’re doing is going to be a big challenge.

Here’s a few things I found helpful:

- It’s natural to be worried about sounding silly in front of your supervisor or your colleagues, but you’ll have to beat this pretty quickly and ask as many questions as you possibly can. Nobody’s expecting you to know everything (or, really, anything) from the get-go, so whenever you come across something you’re not sure about, ask. This is especially true for lab meetings or journal clubs; there will be lots of things you don’t know but you’re surrounded by experts, so just ask them! Sitting in a corner silent and confused is only going to be detrimental to your learning. Get over yourself and sound dumb, it’s good for you.

- The trick to having good ideas is to have lots of them. Most are going to be terrible. Some might not be. Your supervisor can act as a great sounding board for which ideas are probably worth exploring and can translate into work that’ll fit the time (and budget) constrains of your PhD.

- If you think an idea is good, stand by it. Sometimes a good idea is going to get shot down, but that doesn’t mean you ought to abandon it. Take the feedback, refine your reasoning, and try again.

- Likewise, if you’ve been suggested to do something that you don’t think is a good idea, don’t act like you can’t question it just because it came from someone more senior. It’s your project, and you’re spending much more time thinking about it than anybody else. This doesn’t mean you should ignore advice and never listen to anybody else but sometimes you’ll just have to weigh things up and arrive at your own conclusions.

- If you’re not sure how you’re doing - ask! Have a chat with your supervisor and ask them how they think you’re doing. Remember your success is in your supervisor’s best interest, and you taking ownership of your project is a crucial aspect of becoming an independent scientist - so they’ll want to help1.

Scary as it might be, taking ownership of your project is honestly one of the most rewarding aspects of a PhD. Take the plunge and it’ll pay off!

Plan, plan, plan

You know the old adage “if you fail to plan, you plan to fail”? You’re going to have to take it pretty seriously because a PhD is not a whole lot of time2, especially if experiments are involved. Everything is going to take a lot longer than you expect, and going at it without a plan at all is a recipe for a whole lot of anxiety and disappointment.

That doesn’t mean your planning has to be perfect. For the most part, it just has to be. Planning forces you to confront the practical realities of whatever experiment or research direction you and your supervisor have come up with. Coming up with experiments (or analysis) is easy. Actually doing them is a whole other kettle of fish. Coming out of a “jam session” with your supervisor with half a dozen ideas for stuff to do and attempting to do all of them them all at once is a recipe for burning out. You’re not immune to this. A PhD is not a whole lot of time, but it’s not a short amount of time either. Firing all cylinders at all times, working >60 hour weeks for years on end, is unrealistic and unsustainable. Ideally, with a bit of planning you can spread the workload a little more evenly and keep a somewhat consistent output. And, when inevitably you do need to push, you can at least have some idea of how long you have to push for.

Unlike something like software engineering where it is conceivable to have a pretty good idea of what the final product will look like a priori, the reality of research is that direction is bound to change frequently and (at times) rather suddenly depending on how experiments go. This is going to be particularly true at the start, when the overall question / hypothesis of your project is bound to be somewhat vague. That’s perfectly fine. At any one time, you can only really plan based on the information you have available. Treat any plan as ephemeral. Aim to review and revise often.

Project management is an infinite internet rabbit hole. There is an incredible amount of resources and opinions about how to best plan a project or manage your time out there, but I personally find a lot of it quite useless. Most of it appears to cater to a sense of feeling productive without necessarily being productive. But you should explore around and come to your own conclusions; different things work for different people. A few concepts I personally find useful:

- The five year plan. I’m not saying that you should be running your PhD project like a Soviet factory, but I’m not saying you shouldn’t be either. The idea here is that project planning should be done at different levels - across your PhD (4/5 years), the upcoming year, the next few months, the next week and, finally, the day ahead of you3. These different planning levels have different scopes; what you would like to achieve across your PhD is going to be different in magnitude than what you want to achieve by the time you go home today. Planning for longer than what’s immediately in front of you helps to keep what you’re doing in perspective, and also keeps you from losing the forest for the trees. It’s a great way to get rid of tasks / experiments that don’t directly feed into the bigger picture, particularly when you have a lot on your plate.

- Milestones. Coming up with milestones during any long project is a good idea not just to keep things focused, but also to keep motivated and get a sense of accomplishment. It also forces you to come up with concrete deliverables when it comes to a particular body of work, be it analysis or a set of experiments. I’ve done X and managed to answer Y is a pretty good feeling.

- Planning backwards. Once you’ve identified a milestone, when it comes to the actual scheduling of things I find it’s better to start at the end - what the final thing looks like - and work backwards from there. This will force you to think through the interim steps you need to achieve a particular goal, which would otherwise crop up unexpectedly.

- Time blocking. As simple as it sounds, I find this to be extremely effective (when I actually manage to pull it off, which in all fairness is not that often). Block time in your calendar to do one thing, and do it well. Do nothing else during that time. Keeps the mind focused so you don’t have to constantly context switch, which is both tiring and counter-productive. Also a great way to plan the week ahead so that you don’t have to think about what it is you’re supposed to be doing every morning and make sure you’re spending enough time doing things you actually need4 to do.

Vitae, the UK non-profit supporting career development for researchers, has some excellent resources on planning your PhD project, including lots of practical advice on how to get started.

Every meeting needs an agenda

Walking into any meeting without a sense of purpose is inevitably going to be a massive waste of your time. Supervisor meetings, meetings with your colleagues, lab meetings, team meetings - if you’re there, you need to get something out of them, otherwise you’re wasting your time. Particularly for one-on-one meetings, I got a more lot out of them once I started formalising why I was there to begin with. Getting into the habit of jotting a few bullet-points down just prior - for things to discuss, ask or get feedback on - doubles as a great way to keep meetings focused and prevent conversations from going off the rails.

Supervisor meetings in particular become infinitely more useful once you realise they’re not for you to justify your existence5. They are there for you to get feedback on your work. Going over a laundry list of every single task you’ve done since the last meeting is only helpful if your aim is to sound busy. Having a preconception for what you’ll find most useful out of a meeting will ensure it becomes time well spent, and also makes it feel somewhat less intimidating.

Let failure wash over you

If you’ve made it this far, you’ve more than likely gotten used to feeling smart. You’ve done well at school. You’ve probably done quite well at University. Hell, you got into a PhD programme, and that’s as smart as they come.

Unfortunately, if you’re anything like me in 2018, your academic success so far hasn’t prepared you particularly well for dealing with being an idiot. I mentioned earlier that I found my first PhD year the hardest. Frankly, I really struggled to grasp a lot of the literature6. I also was not great at the experiments, and was rather intimidated by a lot of the surgery I had to do. I was very wrong very often. And all my colleagues looked like they really knew what they were doing in a way that I really could not relate to.

How can this be if I am the smartest boy?, I cried.

One of the more confronting aspects of my PhD was realising that I was not, in fact, the smartest boy. It’s very easy, given the nature of the work, to take failure and being wrong personally. This can quickly spiral to feelings of inadequacy, or feeling like you’re an imposter - everyone around you is just so much better and you were a fool to think you could do this to begin with.

The reality is that, unlike what you might have been lead to believe, science is not filled with people of superhuman intellect7. It’s just filled with people. People who have been trained to do a job and have gotten good at it over time. People who are wrong frequently and find science difficult.

And you’ll be one of these people too. Get used to being wrong and don’t take it too personally. It’s just part of the process; you’re working on the frontier of human understanding for crying out loud. And sometimes there will be people who genuinely are a bit smarter and better than you, and for whom it all appears easy. Good on them! My advice is to not fret about that sort of thing and just get on with it.

Get comfortable feeling confused. Let failure reassure you. Celebrate how dumb you are. You’ll be much happier for it.

Bite more than you can chew

A PhD is at its core a training programme - it’s effectively an apprenticeship for being a research scientist. So you should take this time to learn, upskill, and be a bit experimental (no pun intended). And take a few risks.

The PhD is not intended to be comfortable. Unless you’re coming in with a lot of prior experience (e.g. you’ve worked in industry for half a decade or something), you should be feeling well outside your comfort zone. You’ll be doing a lot of things which are new and difficult, all at the same time.

It follows, then, that if you’re feeling comfortable you’re probably not learning a whole lot. Booo! You should live a little. Take a side project on. Go teach. Learn a new technique, or stats, or programming. It’s all going to be useful down the line, and you’ll meet new people and make connections and, if the unthinkable does happen and you decide to one day leave academia, you’ll have a bunch of useful skills to take with you.

Strictly speaking, all you need to do to get a PhD (in the UK at least) is write a thesis. In this respect, what is expected of you during your PhD hinges entirely on your own progression. Contrast this with being a postdoc or research assistant, where you’re contractually obliged to deliver things like papers and grant proposals and pilot data. Take advantage of the time you have and max out on the things you can do and learn!

But, you know, don’t overdo it and burn out. That’s no good. If you’re having trouble getting out of bed or being motivated you might want to scale some of your extracurriculars back and just focus on the thesis itself. It’s an opportunity, for sure, but it’s really not worth sacrificing your health over.

Keep a research journal

Look, everyone probably keeps telling you this, but you really should write down the things you’re working on. It might seem whatever it is you’re working on is just too important to forget, but trust me, it isn’t and you’ll forget about it. Maybe not next week, maybe not next month, but a couple of years down the line you’ll be staring at a plot wondering where the hell it came from.

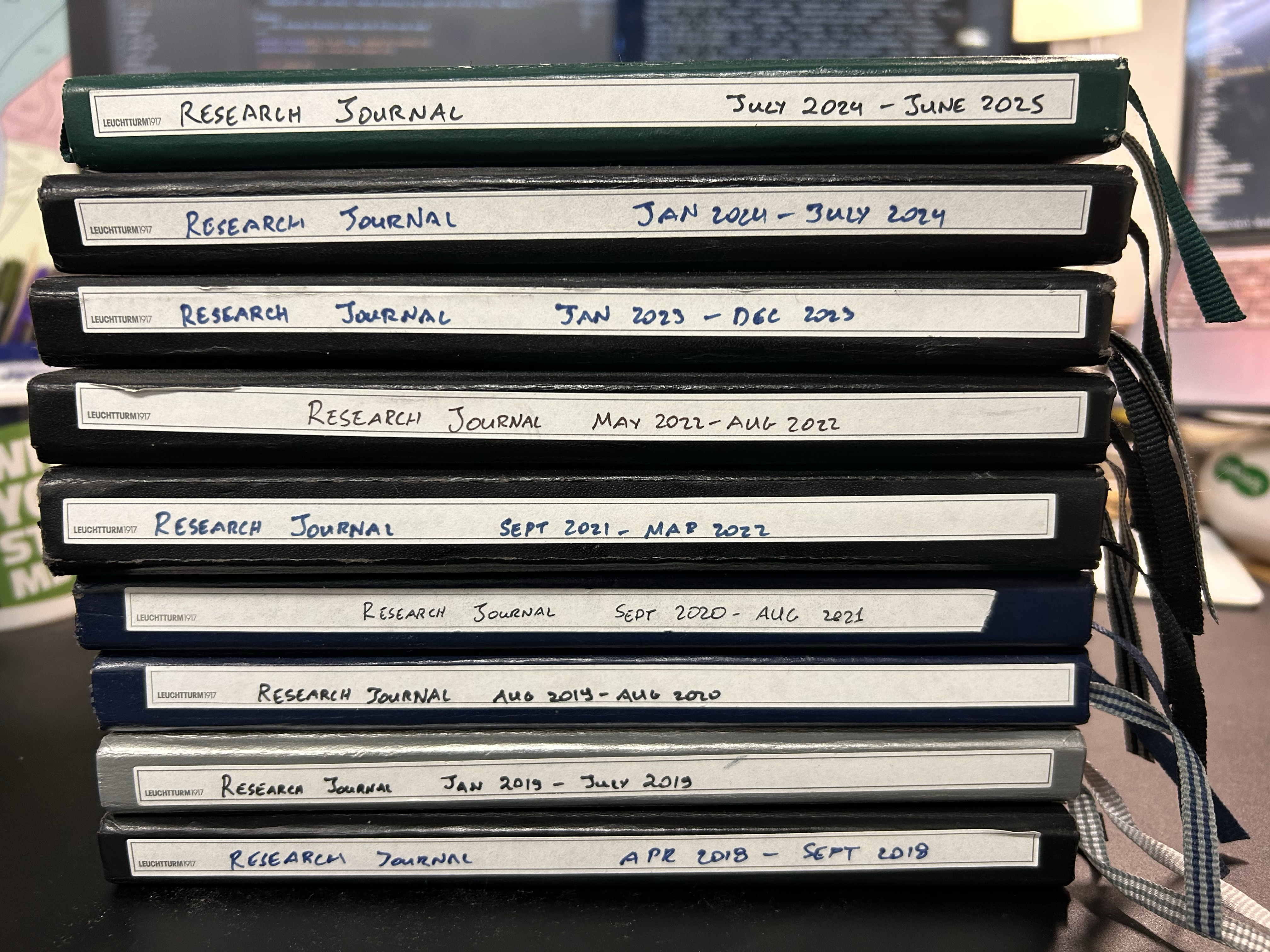

After some trial and error, I settled on keeping “research journals” in physical notebooks. Think of them as diaries for the research. I love my stationery, and writing things down on paper offers a welcome break from staring at screens all day. You’ll come across a cacophony criticisms for paper if you look online - what if you lose your notebook! paper isn’t searchable! - but honestly I’ve not lost a notebook yet and flicking through old ideas looking for something I did long ago is both kinda fun and leads to unearthing a lot of worthwhile stuff I’ve forgotten about.

It doesn’t really matter how you do it, but I would suggest you avoid enforcing too much structure on your notes. Treat them as scribblings, not as polished products; save the polish for your papers and your thesis. The important thing is that you write things down, not that they look pretty or organised. All you really need is a date at the top.

I keep a lot of notes on meetings, random ideas that pop in my head, as well as things like planning bits of analysis or experiments. I differentiate between my “research journals”, which are for personal scribblings with no particular structure to them, and lab notebooks, which are much more structured and contain the kind of experimental information we’re legally bound to keep. The specific policy on the latter will likely vary based on your department; your research journal on the other hand is for you, so you can do whatever you want with it.

Show up

Pretty much what it sounds like. I know it might come across a bit silly, but you should make an effort to physically be there during your PhD.

It is incredibly, incredibly easy to become extremely siloed during you PhD, even if it requires your physical presence (i.e. you need to do experiments). You might feel like you’re out of time, or you concentrate better on your own, or like to work in your jimjams… Whatever the reason, you may find yourself spending less and less time around your colleagues and more time on your own, either at home or in some dark recess of whatever 18th century cavern you happen to be working in.

Honestly, don’t.

People are different, and people’s “optimal” working conditions vary. But we humans are social creatures. Isolation will not do you good, neither mentally nor professionally. Your colleagues are probably the only people around who’ll know what you’re going through, and blowing off some steam having a rant about things being a bit shite is honestly quite therapeutic.

Science is the friends we make along the way. Show up, talk to people, be nice. It’s good for your soul.

Not every PhD is the same. There’s a very solid chance that your experience was or will be quite different from mine. But I genuinely hope that you’ll find at least some of this useful. If you’re just starting up your PhD, or are well into it, and are finding it difficult, don’t fret. It’s all perfectly normal. Anyone who tells you they found it easy is lying and you should tell them to go away.

You got this.

Don’t do what I do, basically. pic.twitter.com/3WCbI1e9w6

— Dr Meming (@Dr_Meming) August 31, 2024

And much like my PhD, this blog post got a bit too long and took me way longer to write than I thought it would.

Thanks again to Austin Henley for the inspiration!

-

I’m assuming your supervisor will earnestly want to be helpful because this was my experience, but unfortunately this isn’t always going to be the case. Not all supervisors are good mentors. There’s a few ways you can sort of gauge this before starting a PhD but that’s a matter for a different post. ↩

-

The usual PhD funding in the UK for a neuroscience PhD programme is ~4 years. ↩

-

I remember coming across this concept a while back described as planning at “10k ft, 1k ft, 100 ft” etc but I could not find a good resource when writing this post for the life of me. It’s practically the same thing. ↩

-

“Need” can take a variety of definitions, but generally speaking - you need food and water, you don’t need to spend half a morning trying to work out why the Zotero plugin doesn’t work on Safari anymore. ↩

-

If you’re in a meeting where you need to justify your existence, you generally know before you rock up to the meeting. ↩

-

By this point in my life/career, if I don’t understand a paper, I blame the authors. If the half dozen people in your field who would care about your paper don’t understand what you’re on about then who did you write this for? ↩

-

Don’t meet your heroes, kids. ↩